Intro

AI has rapidly evolved from science fiction into a practical tool accelerating real scientific breakthroughs. In laboratories and research centers around the world, AI systems are crunching data, designing experiments, and even formulating hypotheses. Nowhere is this transformation more apparent than in the life sciences, where AI-driven approaches are helping to unravel complex biological systems, discover new drugs, and decode the secrets of life.

This post takes a high-level journey through the history of AI in scientific research, highlights how we arrived at today’s AI-powered discoveries, and profiles key players (such as FutureHouse, Lila Sciences, and Biomni) leading the charge. We’ll also glance at how AI is influencing other scientific fields like chemistry and materials science for context, before concluding with a forward-looking view of what the next 5-10 years may hold.

From Expert Systems to Early AI Researchers (1960-2010)

DENDRAL - 1960s

The idea of using computers to aid scientific discovery dates back decades. In the 1960s, pioneers developed some of the first expert systems to tackle scientific problems. A famous example is DENDRAL, a project at Stanford that helped chemists deduce the structures of organic molecules from mass spectrometry data.

DENDRAL (DENDritic Algorithm) is often considered the first AI system for scientific research. Its primary purpose was to discover a chemical’s structure from its mass spectrum. Given a histogram of fragment abundance, DENDRAL identifies the original structure.

Although DENDRAL doesn’t qualify as AI by today’s standards (it didn’t learn from data or adapt over time) it was still able to replicate expert-level chemical reasoning through hardcoded rules and logic. By combining domain-specific heuristics with combinatorial search, DENDRAL could deduce molecular structures from mass spectrometry data in ways that mirrored human scientists. It demonstrated that machines could assist in scientific inference, making it a foundational step toward more dynamic AI systems that followed.

ADAM - 2009

Fast forward to the 2000s, and AI had graduated from solving narrow tasks to tackling more of the scientific process itself. A watershed moment came in 2009, when a team in the UK unveiled a “robot scientist” named Adam. Adam was a laboratory robot powered by AI that not only managed data but could autonomously generate hypotheses, run experiments, and interpret results. Essentially executing the scientific method on its own.

Adam was a rule-based system that integrated a knowledge base of yeast biology with automated hypothesis generation, experiment planning, robotic execution, and data analysis. It used logical inference and probabilistic reasoning to identify gaps in known gene functions, then designed experiments to test those hypotheses using lab robotics. While it didn’t learn from data in the modern machine learning sense, Adam represented an early example of an end-to-end computer-driven scientific workflow, showcasing how symbolic reasoning and automation could emulate aspects of the scientific method.

In a study on yeast genetics, Adam independently hypothesized the functions of several genes, conducted experiments via robotics to test these hypotheses, and confirmed new scientific knowledge about the organism. This achievement, the first time a machine discovered new biological knowledge without human guidance, was a milestone. As Stephen Oliver, one of Adam’s creators, noted, the big deal with Adam was that it showcased a machine’s ability to reason over data and propose how a living system works. It foreshadowed a future where human and AI “scientists” work together to handle the growing complexity of biological research.

The Deep Learning Revolution in Science (2010-2020)

If early AI in science was defined by rule-based systems and robotics, the 2010s ushered in a revolution driven by machine learning and deep learning. Several technological breakthroughs enabled modern AI systems to truly transform scientific discovery:

Explosion of Data: Modern science generates vast datasets, from genome sequences and medical images to astronomical observations. This “big data” provided fertile ground for AI. Machine learning algorithms trained on large datasets began outperforming humans in pattern recognition tasks (for example, identifying cells in microscope images or spotting anomalies in telescope data).

Advances in Algorithms: Deep learning (neural networks with many layers) gave AI a far more powerful pattern-finding tool. By around 2012, deep neural networks were breaking records in image recognition and language understanding. Scientists soon applied these techniques in bio (for example, analyzing pathology slides or MRI scans), chemistry (predicting chemical reactions), and more. AI moved beyond data analysis toward generating new insights from complex patterns, such as

Identifying previously unknown gene-disease associations in genomic data

Predicting the outcomes of chemical reactions and proposing new synthetic pathways that chemists hadn’t yet considered.

Increased Computing Power: The rise of GPUs and cloud computing made it feasible to train massive AI models on scientific data. Complex models that once took months to train could be run in days or hours, accelerating the research cycle.

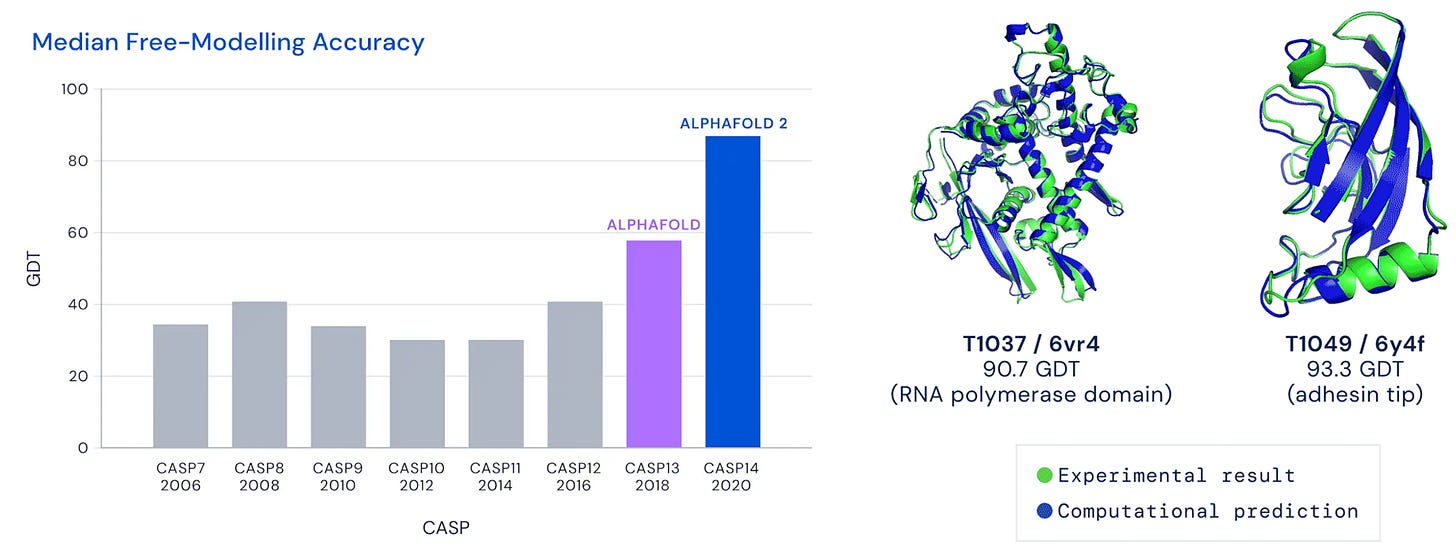

Of the most popular scientific breakthroughs showcasing these advances was DeepMind’s AlphaFold. In late 2020, AlphaFold2 stunned biologists by computationally predicting protein 3D structures with astonishing accuracy — something scientists had struggled with for 50 years. At a prestigious protein-folding competition (CASP 2020), AlphaFold2 achieved a median Global Distance Test Total Score of 92.4 on the free-modeling targets in CASP14, clearing the competition and also matching proven experimental methods for determining protein structure like X-ray crystallography.

Not only did Alphafold show promise in improving the accuracy of protein structure prediction, but in doing so computationally, it makes the whole process many times faster and less expensive, which can significantly expedite the development of new therapies.

The organizers proclaimed that AlphaFold had “largely solved” the long-standing protein folding problem, shifting protein science forever. In practical terms, AI cracked a grand challenge of biology, producing in days structural insights that often took wet-lab experiments years. This success was hailed as one of the biggest AI-driven breakthroughs in science to date, and it opened the floodgates for using AI in other fundamental scientific problems.

AlphaFold’s achievement was enabled by deep learning and massive data, but it also highlighted a new paradigm: AI as a creative problem-solver in science, not just a data cruncher. Soon, generative AI models began designing new molecules for drugs, and language models trained on scientific texts started answering complex research questions. The stage was set for AI to become a true partner in discovery.

AI in Life Sciences: Transforming Biology and Medicine (2020-)

Biology today involves hugely complex datasets (genomic sequences, proteomic data, medical images, electronic health records, and more) that are difficult to interpret without computational help. AI is rising to the challenge across multiple fronts:

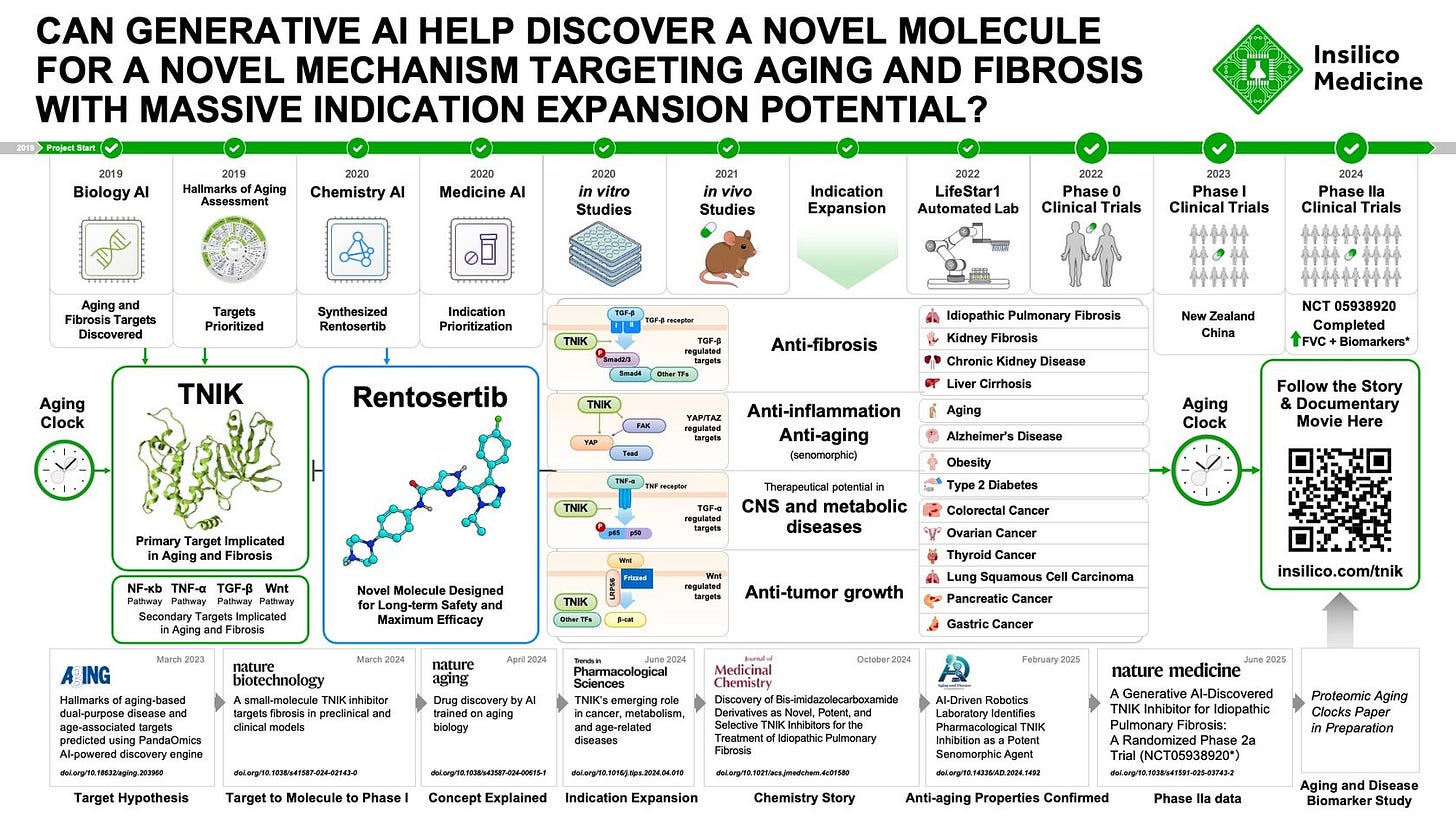

Drug Discovery: Perhaps the most publicized impact has been in discovering new therapeutics. AI algorithms can screen billions of chemical compounds, predict which molecules might become effective medicines, and even design novel molecular structures from scratch. In early 2020, UK-based company Exscientia (now acquired by Recursion) announced the first AI-designed drug candidate to enter human clinical trials: a molecule for treating obsessive-compulsive disorder. Since then, several companies like Insilico Medicine have advanced AI-designed drugs into trials. In total, as of the early 2020s, around 15 AI-discovered drug candidates were reportedly in clinical development, with dozens more in earlier stages. This rapid progress suggests AI is speeding up the drug pipeline by suggesting better drug targets and molecule designs.

For example, Insilico Medicine used AI to design a novel drug for pulmonary fibrosis that rapidly progressed to Phase IIa clinical trials, where it was tried in human patients and demonstrated safety and efficacy, marking a significant acceleration compared to the typical multi-year drug development timeline. While it’s still early days for AI-developed medicines, the approach is promising. AI systems can explore chemical space far more quickly than traditional lab experiments, potentially uncovering treatments human scientists might miss.

The Rise of Multimodal Foundation Models in Drug Discovery

The early 2020s have seen a surge in multimodal foundation models tailored to drug discovery. These models, trained on large datasets combining chemical structures, protein sequences, assays, and literature, unified diverse drug discovery modalities within single architectures.

AlphaFold2 (DeepMind, 2020): Revolutionized protein structure prediction by accurately modeling 3D structures from amino acid sequences. Its database expansion and widespread adoption in drug discovery workflows surged in 2022–2023, enabling rapid target characterization.

ESMFold (Meta, late 2022): Achieved fast, high-accuracy protein structure prediction directly from sequences using a 15-billion-parameter protein language model without explicit 3D supervision, helping scale protein target analysis efficiently.

ProGen (Salesforce Research / Stanford, 2020): Leveraged language models trained on large protein sequence datasets to generate novel, syntactically valid, and biologically functional proteins, expanding possibilities for therapeutic biologic design.

DiffDock (MIT, 2022): Introduced a diffusion-based generative model to predict small molecule docking poses, outperforming traditional docking methods with better binding accuracy and success rates.

ProteinMPNN (Baker Lab - UW, 2022): A graph neural network approach for designing protein sequences conditioned on backbone structures, enabling efficient, accurate design of functional proteins on given scaffolds.

Platforms like Tamarind Bio have made these models easily accessible, providing no-code tools and APIs to run state-of-the-art protein prediction, design, and docking models in the cloud.

Genomics and Precision Medicine: The cost of DNA sequencing has plummeted, leading to massive genomic databases. AI is crucial for sifting through this genomic data to find disease-causing mutations or personalized treatment strategies. Machine learning models are used to predict which genes are implicated in a disease or how a specific patient might respond to a given drug. In research, AI has helped prioritize causal genes in complex diseases and identify new biological pathways. For instance, deep learning models have been trained on cancer genomes to predict patient outcomes and guide targeted therapies. As a step toward precision medicine, AI can match patients to the treatments most likely to help them based on patterns in their genomic and clinical data.

Medical Imaging and Diagnostics: Image-recognition algorithms (especially deep convolutional neural networks) have revolutionized analysis of medical scans and microscope images. In radiology and pathology, AI systems can flag tumors or other anomalies on X-rays, MRIs, and biopsy slides with accuracy comparable to experts. Such tools are speeding up diagnosis and may soon assist doctors in identifying diseases earlier. In ophthalmology, for example, AI is used to detect diabetic retinopathy from retinal images with high accuracy, helping prevent blindness through early intervention. AI diagnostic assistants are emerging in dermatology, neurology, and many other specialties.

Laboratory Automation (“Self-driving labs”): Building on the concept proven by the Adam robot scientist, today’s labs are increasingly incorporating AI with robotics to create automated research workflows. Startups and research groups are developing “self-driving labs” where AI plans experiments, robots execute them (e.g. pipetting liquids, running assays), and then AI analyzes the results to decide the next experiments, all with minimal human input. This closed-loop system can iterate experiments faster than humans, optimizing conditions to achieve a research goal. For example, a lab might use an AI-driven system to test thousands of enzyme variants to find a biocatalyst for a new chemical reaction, with the AI adjusting parameters on the fly to hone in on the best variant. Such approaches are accelerating research in synthetic biology and chemistry. As one researcher quipped, these AI lab assistants are like having a tireless 1st-year grad student who can run experiments 24/7, except much faster.

EHR and Clinical Administration

AI is transforming EHR and clinical administration, led by major platforms like Epic, Oracle Health, Athenahealth, and eClinicalWorks—each using AI for note-taking, workflow automation, predictive analytics, and billing efficiency. We’re also seeing an influx of startups tackling niche areas within this industry:

Nabla – AI medical co-pilot that summarizes real-time patient encounters for physicians.

Moxe Health – Streamlines data exchange between payers and providers using AI to reduce documentation and authorization burdens.

Awell Health – Builds workflow automation for clinical care pathways, enabling dynamic protocol execution inside EHRs.

Glass Health – Focuses on AI-powered clinical decision support and medical knowledge graphs for diagnosis and treatment planning.

Hippocratic AI – Developing safety-first LLMs for non-diagnostic, administrative healthcare tasks like patient follow-up calls and eligibility checks.

One of the most ambitious examples in the life sciences today is Biomni, a project out of Stanford introduced this year.

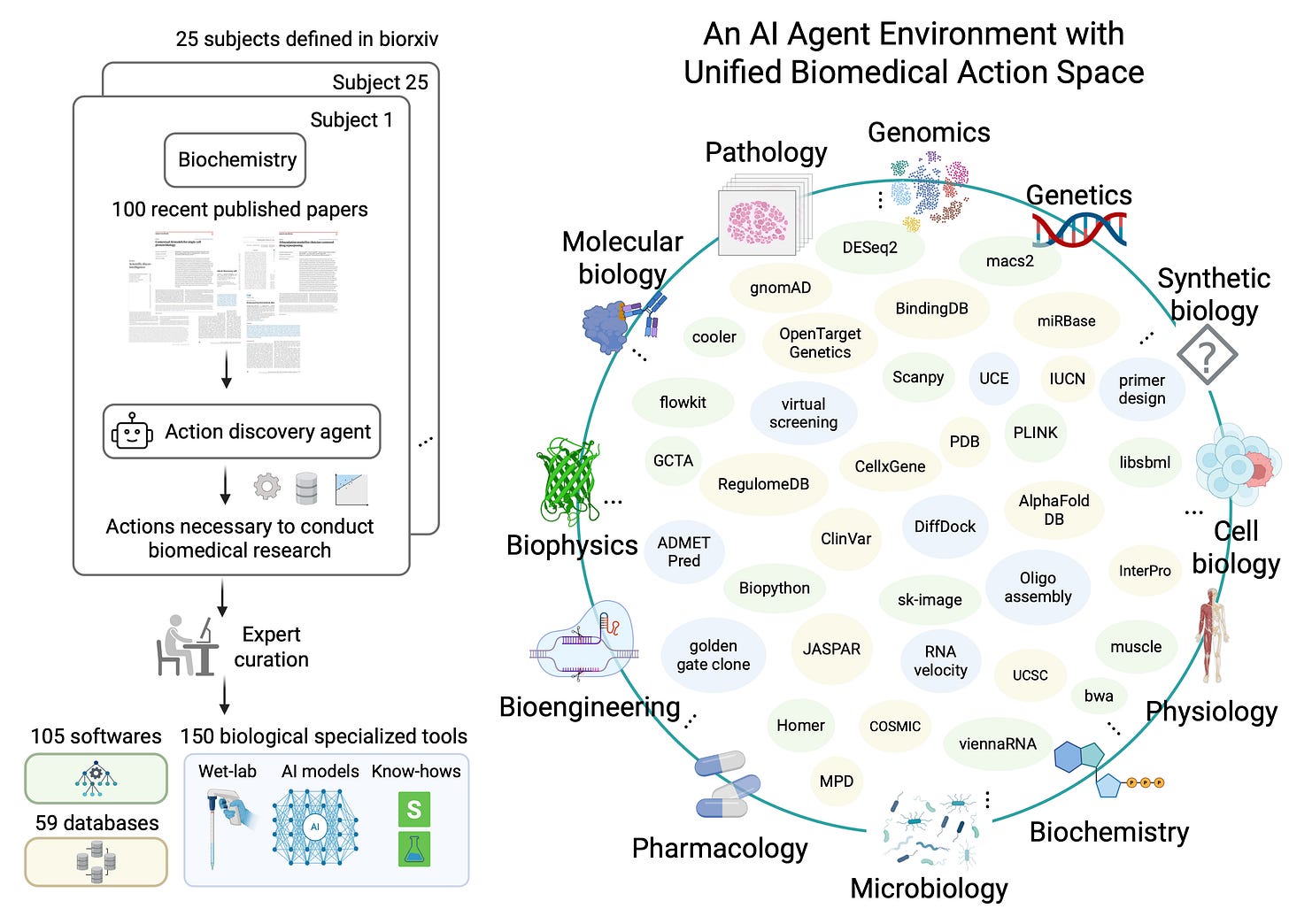

Biomni is described as a “general-purpose biomedical AI agent” that can autonomously execute a wide range of research tasks across biology and medicine. Unlike AI tools trained for one narrow task, Biomni was built to be a virtual AI scientist for biomedicine. It works by integrating a large language model with a suite of scientific databases, software tools, and even the ability to generate and execute code.

In practical terms, Biomni can dynamically plan out complex biomedical workflows on the fly, without pre-programmed scripts, and carry them out end-to-end. Researchers have demonstrated it performing tasks as varied as identifying candidate genes linked to a disease, suggesting existing drugs that might be repurposed for new conditions, diagnosing rare diseases from symptoms, analyzing genomic and imaging data together, and drafting detailed laboratory protocols for experiments. All of this is done autonomously, with the AI agent deciding which tools or databases to invoke as it composes a solution.

Early benchmarks show Biomni generalizes well: it achieved human-level performance on several biomedical challenges and dramatically sped up complex analyses. In one case study, Biomni analyzed a wearable sensor dataset in 35 minutes vs. 3 weeks that human experts had needed (an 800× speedup). In another, it designed a molecular cloning experiment that matched the work of a PhD-level biologist with 5+ years of experience (read more: anthropic.com).

While Biomni is still new, it embodies the cutting edge of AI in life sciences: systems that augment human scientists, handling the grunt work at superhuman speed so that researchers can focus on higher-level insights. The vision, as the Biomni team puts it, is a future of virtual “AI biologists” working alongside humans to dramatically expand the scale and productivity of research.

Major Players Driving AI-Powered Autonomous Scientific Research

The rapid progress in AI and science has spurred a diverse ecosystem of players: from tech giants and startups to academic institutes and nonprofits. Here I highlight some of the major organizations and projects at the forefront of AI-driven discovery, particularly in the life sciences:

FutureHouse: Founded in 2023, FutureHouse is a new nonprofit research lab with a moonshot mission: “to build an AI scientist within the next decade.” Backed by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, FutureHouse is assembling a team of AI researchers and biologists in San Francisco to create AI agents capable of automating scientific discovery. Their focus is initially on biology and chemistry. In 2025, FutureHouse introduced an AI tool called Finch that exemplifies their approach. Finch takes in research data (for example, a collection of biology papers or a genomics dataset) and a natural-language prompt (such as “What are the key molecular drivers of cancer metastasis?”). It then writes and runs code to analyze the data, produces relevant figures or results, and presents an answer. Finch behaves like an automated researcher that can perform multi-step data analysis in minutes, something that might take a human scientist weeks, all guided by an AI brain. The long-term aim is to keep improving these AI agents (Finch is an early prototype) until they can handle much of the scientific process independently. While FutureHouse’s tools have not yet yielded a major novel discovery, the organization is closely watched as a leader in the AI-for-science movement. Its nonprofit status also underscores an interesting point: some view AI-driven science as so important to humanity’s future that it merits philanthropic support to ensure the technology is developed responsibly and for the public good.

Lila Sciences: Lila’s approach centers around building symbolic-biological hybrids – combining neural models with explicit representations of biological knowledge, such as pathway diagrams or gene regulatory networks. This makes their systems more interpretable and potentially more capable of hypothesis generation, as opposed to pure statistical inference. In their early prototypes, Lila has demonstrated tools that ingest structured biomedical data and textual sources, and then output graphical causal diagrams that resemble human-drawn models used in systems biology.

They're working on an AI-driven physical laboratory that will automate the scientific method through continuous iteration and improvement. You would be able to initiate an optimized experiment with an API call.

The team at Lila has also emphasized the importance of explainability and collaborative tooling. Rather than aiming to fully automate research, they are building tools designed for scientists studying biology, chemistry, and materials science to explore, critique, and refine AI-generated models. In that sense, Lila’s vision of "AI-native scientific reasoning" is closer to augmented intelligence than autonomous agents – with the goal of accelerating understanding, not just throughput.

As AI systems become increasingly powerful but opaque, Lila’s focus on making models interpretable, causal, and dialogic could play a key role in ensuring that life sciences remain both rigorous and transparent in the age of machine assistance. While still early stage, Lila Sciences represents an exciting direction in the evolving ecosystem of AI-powered discovery.

Biomni (Stanford University): As discussed above, Biomni is a cutting-edge academic project that delivered a powerful, open-source, AI agent for biomedical research. By open-sourcing the system (available at biomni.stanford.edu), the Biomni team has invited scientists worldwide to experiment with having a “virtual postdoc” AI on hand. This could democratize research, allowing smaller labs to leverage AI for complex analyses without massive compute resources. The collaboration between Biomni and companies like Anthropic highlights how industry and academia are joining forces to advance AI in science. Through its partnership with Tamarind Bio, Biomni also gains access to cutting-edge foundation models for drug discovery — including Boltz-2, one of the latest AI models for protein folding that provides a 1,000x speed up over AlphaFold and existing methods in predicting binding affinity.

FutureHouse, Lila, and Biomni represent three distinct yet complementary approaches to AI-augmented science: a nonprofit pursuing open scientific moonshots, a venture-backed startup focused on interpretable reasoning tools, and an academic consortium building general-purpose biomedical agents. Together, they reflect a broader ecosystem converging on the same goal from different angles.

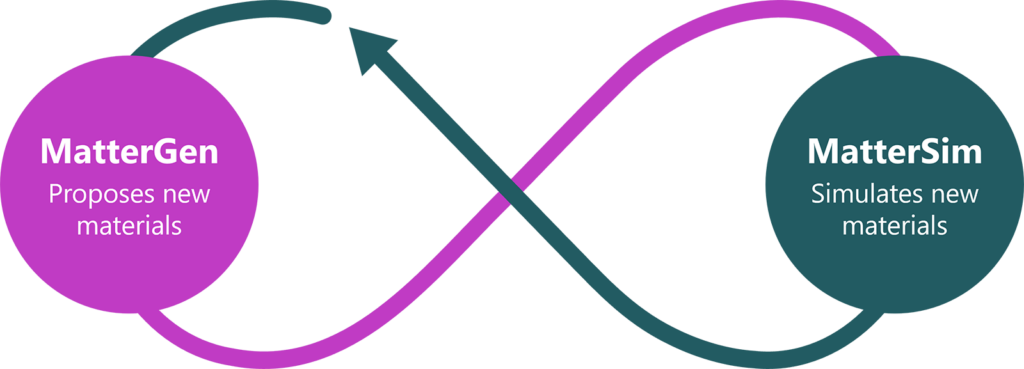

Big Tech in Life Sciences: Several major tech companies are deeply involved in AI for scientific discovery. Google DeepMind, is notable for its contributions to biology, after AlphaFold’s success in predicting protein structures, DeepMind didn’t stop there. It has since released the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, containing predicted structures for nearly all known proteins, and is exploring AI applications in other areas of science. DeepMind’s research has branched into material science as well. For example, it developed an AI system called Gnome that reportedly discovered new crystal structures that could lead to novel materials. Microsoft is also investing in this arena: in recent years, it introduced AI tools like MatterGen and MatterSim, aimed at designing new materials and chemicals via AI.

Microsoft has partnerships with pharmaceutical companies to use its cloud AI for drug discovery, and it’s been integrating AI into its healthcare products (like image analysis for medical imaging). IBM was an early mover with its Watson Health initiative (which had mixed results in oncology), but IBM continues to research AI for molecular discovery and has projects for AI-driven chemical synthesis (like the IBM RXN system for planning chemical reactions). AWS has also entered the space with initiatives like HealthOmics, which provides infrastructure and tools for scalable omics data processing and machine learning–powered biomedical analysis. HealthOmics also enables researchers to run foundation models for drug discovery and other biomedical use cases through services like SageMaker and integrated AI/ML pipelines. Even OpenAI signaled the strategic importance of science: one OpenAI research executive left to start a new AI-driven materials science venture, and OpenAI stated it views “AI for science as one of the most strategically important areas” for achieving future breakthroughs. In short, the tech giants see scientific discovery as a frontier where advanced AI can make a transformative impact, and they are investing talent and resources accordingly.

Together, these players form an ecosystem driving an AI renaissance in the life sciences. Importantly, collaboration is common, startups often partner with pharma companies that have decades of domain data, tech giants provide cloud and AI platforms, and academic groups contribute foundational research and validation. The competition and collaboration between these entities is accelerating progress at a breathtaking pace. It will be fascinating to see how companies building AI scientists integrate these pieces into cohesive, end-to-end systems for scientific discovery.

AI Beyond Biology: A Glimpse into Other Sciences

While our focus is life sciences, it’s worth noting that AI is catalyzing discovery across many scientific domains. Here are a few examples that show the breadth of AI’s impact:

Chemistry: AI models are being used to predict the outcomes of chemical reactions and suggest new synthesis pathways for important molecules. For instance, AI can help chemists design more efficient routes to create a drug molecule or propose novel compounds with desired properties (like a new polymer that is super-strong yet lightweight). In materials chemistry, deep learning has been applied to discover new catalysts for renewable energy and to identify materials for better batteries.

Materials Science: Designing new materials (for electronics, energy storage, aerospace, etc.) often involves expensive trial-and-error. AI is changing that by simulating and optimizing material properties faster. As noted, DeepMind’s Gnome AI found new crystal structures that human scientists hadn’t considered, potentially leading to novel materials. Microsoft’s MatterGen/MatterSim are examples of tools that let researchers virtually “mix and match” atomic ingredients to discover materials with specific traits. In one case, an AI model suggested a new alloy composition that turned out to be extremely heat-resistant, guiding experimentalists to create it in the lab. The field of quantum materials also benefits from AI to identify compounds that could become high-temperature superconductors or better semiconductors.

Physics and Astronomy: As you can imagine, AI’s strength in pattern-recognition is invaluable in physics, where researchers use it to find signals in massive datasets. In particle physics, machine learning sifts through collision data to spot hints of new particles or phenomena. In astronomy, a Google ML algorithm helped NASA identify exoplanets (planets around other stars) by combing through Kepler telescope data. By recognizing the subtle dimming pattern of a star when an orbiting planet passes in front of it, AI found exoplanets that had been missed in earlier analyses. AI has also been used to analyze gravitational wave signals and map the large-scale structure of the universe from telescope surveys. In fundamental physics, there are even efforts where AI systems have rediscovered known equations (like Newton’s laws) from raw experimental data, and hinted at new physical relationships (AI-Newton, 2025). This raises the tantalizing prospect that AI might one day assist in formulating entirely new physics theories.

Environmental and Earth Sciences: Climate science and ecology are embracing AI to handle complex, interconnected datasets. AI helps climatologists improve weather and climate models by learning patterns from decades of atmospheric data, leading to better predictions of extreme events. In environmental biology, machine learning is used to monitor biodiversity (e.g. identifying animal species from camera trap images or audio recordings of bird calls). It’s also used in geology, for example, AI algorithms help process seismic data to predict earthquakes or to locate new mineral deposits by finding subtle geologic signatures.

These examples underscore a key point: AI is a general catalyst for scientific discovery. Whether the goal is to find a new drug, a new material, or a new solar system, the core strengths of modern AI: handling immense data, spotting patterns, and optimizing complex systems are broadly applicable. Different fields pose different challenges, but advancements in one domain often carry over to others. For instance, improvements in AI algorithms for image recognition (pioneered in computer vision) help both biologists analyzing cell images and astronomers scanning the skies. Similarly, natural language processing advances that allow AI to “read” scientific papers can benefit all disciplines by connecting insights across literature.

The Next 5-10 Years: Challenges and New Frontiers

What does the future hold for AI-driven scientific discovery, especially in the life sciences, over the coming decade? In many experts’ view, we are on the cusp of an unprecedented acceleration in how science is done, but there are also significant challenges to overcome. In this forward-looking section, we’ll explore emerging technologies, potential hurdles, and new frontiers that could define the next 5-10 years:

1. From Assistant to Autonomous Scientist: Today’s AI tools largely act as smart assistants; they perform specific tasks very well and help researchers make sense of data. In the next decade, we may see AI systems graduate to more fully autonomous scientists. This means an AI might handle entire research projects: formulating a hypothesis, designing and conducting experiments (virtually or with robots), analyzing results, and even deciding when a discovery is significant enough to publish. Early versions of this vision exist (as we saw with Biomni and FutureHouse’s Finch). By 2030, these systems will likely be far more advanced, possibly able to run closed-loop experiments continuously with minimal human input. Self-driving laboratories could become common in biotech and pharma companies, an AI system could be told to “find a molecule that inhibits protein X” and it will orchestrate computational models and robotics to synthesize and test thousands of candidates, iteratively honing in on a solution. This autonomy could dramatically speed up R&D cycles in medicine and other fields.

2. Multi-Modal and Multidisciplinary AI: Future AI scientists will be multi-modal. That is, capable of understanding different types of data (text, numbers, images, genetic sequences, etc.) simultaneously. In life sciences, this is crucial: a complete picture of biology involves genomic data, experimental results, clinical observations, and literature knowledge. We can expect AI models that unify these modes, finding connections that a specialist might miss. For example, an AI might read millions of journal articles, analyze genomic databases, and examine clinical trial results together to propose a novel theory for treating Alzheimer’s disease. These AI systems would effectively break down silos between subfields, fostering more multidisciplinary discoveries.

There is also growing momentum around multi-modal AI interfacing with simulation tools. By combining language models with physics-based engines (such as those used in molecular dynamics or cell modeling), AI agents can query, steer, and interpret complex simulations in real time. Biomni is a great example of this. This allows for more intelligent in silico experimentation, where reasoning over models, parameters, and outputs is tightly integrated with scientific understanding, accelerating hypothesis testing and optimizing wet-lab designs.

3. Collaboration between AI and Human Scientists: Rather than AI replacing scientists, the next decade will likely see a deepening collaboration between them. Human creativity and domain expertise combined with AI’s relentless analytic power will be a potent mix. We’ll need new interfaces and ways of working to facilitate this teamwork. One emerging idea is the “co-pilot for scientists”, which is analogous to how software developers now have AI coding assistants like Cursor and Windsurf. A scientist could have an AI collaborator that watches their work, offers suggestions (“Have you considered this gene pathway?”), or automatically handles routine tasks like drafting the methods section of a paper, ordering materials for an experiment, or replicating previous work. This raises human productivity and can also serve as a check: the human monitors the AI’s suggestions for sense and significance, while the AI ensures the human doesn’t overlook relevant data or known results. In fields like medicine, clinicians might work with AI to plan treatments: the AI proposes personalized options drawn from vast data, and the doctor makes the final call in consultation with the patient. In essence, a symbiosis where AI amplifies human ingenuity.

4. New Frontiers and Moonshots: Several tantalizing scientific quests could be unlocked by AI in coming years. One is the search for cures to complex diseases like cancer, Alzheimer’s, and autoimmune disorders. AI’s ability to parse enormous biological datasets may yield new insights into disease mechanisms and thus new therapeutic targets. In fact, optimistic voices in tech have speculated that sufficiently advanced AI might help “formulate cures for most cancers” by identifying patterns across cancer types and vast compound libraries, though this remains to be seen. Another frontier is understanding the brain: efforts like the Human Brain Project have collected mountains of neural data, and AI models (especially neural networks) might be key to deciphering how cognitive processes emerge, potentially guiding advances in neuroscience and treatment of mental illness. Beyond health, AI could drive breakthroughs in sustainability. For instance, discovering efficient methods to capture carbon or create clean energy materials, crucial for combating climate change.

5. Challenges - Hype vs. Reality and Trustworthiness: With all the excitement, it’s important to acknowledge the challenges. As of 2025, many scientists caution that AI hasn’t yet delivered truly novel theories or paradigm-shifting discoveries on its own. In other words, AI is great at optimization and pattern recognition, but the creative leaps in science often still come from human intuition. It may take time for AI to mature from an assistant to an originator of deep scientific insights. Additionally, current AI models can make mistakes, sometimes confidently. Issues like hallucinations or overfitting (seeing patterns that aren’t real) mean that human oversight is crucial. Below is a thoughtful critique of some of FutureHouse’s recent claims around AI-powered scientific discovery, particularly their framing of novelty, closed-loop experimentation, and what counts as a breakthrough:

The scientific community will need to establish standards for validating AI-generated results, to ensure that discoveries are genuine and not artifacts of a flawed algorithm. There’s also the matter of interpretability: scientists are rightly wary of “black box” models. If an AI suggests a new drug target, researchers need to understand why to trust it. Thus, making AI models more transparent and explainable is an active area of work. Finally, ethical considerations cannot be ignored. AI-driven research must handle sensitive data (like patient records) with privacy in mind, and society will need to grapple with questions like patenting AI-discovered drugs or attributing scientific credit when an AI contributes to a discovery.

Despite these challenges, the trajectory is unmistakable. The coming years will likely bring AI systems that are smarter, more reliable, and more deeply integrated into the fabric of scientific research. Leaders in the field are extraordinarily bullish about the potential. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, has said that superintelligent AI (if achieved) could “massively accelerate scientific discovery and innovation,” perhaps leading to a new golden age of science. Even in the near term, incremental improvements in AI capabilities could yield a cascade of benefits: faster drug approvals, more accurate disease diagnostics, new materials for technology, and a better fundamental understanding of life and the universe. Importantly, regulatory agencies like the FDA have signaled increasing openness to AI, issuing guidance on machine learning in medical devices and piloting frameworks for AI-assisted drug development.

Conclusion

The evolution of artificial intelligence in scientific discovery has been a journey from simple rule-based programs to complex agents that can reason, experiment, and learn. In the life sciences, AI is transitioning from a helpful tool to a true collaborator: handling data deluge, suggesting insights, and even carrying out experiments. We’ve seen how historical efforts like expert systems and the first robot scientists paved the way, and how modern breakthroughs such as deep learning and projects like AlphaFold proved AI’s prowess on grand challenges. Today, an ecosystem of innovators, from academic consortia building general AI scientists like Biomni, to nonprofits like FutureHouse, tech giants, and biotech startups, are collectively pushing the boundaries of what AI and humans can discover together.

While we must remain cautious about the hype and address the limitations of current AI, the momentum is undeniable. AI is helping scientists ask bolder questions and tackle problems once thought intractable. In biology and medicine, this could mean new cures, personalized treatments, and deeper knowledge of life. In other fields, it promises cleaner energy, smarter materials, and perhaps insights into fundamental physics. The next 5–10 years will be crucial in translating AI’s impressive capabilities into everyday scientific practice. If we succeed, we may look back on this period as a turning point when the very nature of scientific discovery changed, a time when we embraced intelligent machines as partners in expanding humanity’s understanding of the world and solving its most pressing problems. The age of AI-driven discovery in the life sciences has only just begun, and its future is as exciting as it is profound.

References

Feigenbaum, E.A., et al. (1965). DENDRAL – Stanford’s pioneering AI system for chemical analysis en.wikipedia.org.

University of Cambridge (2009). Robot scientist Adam discovers new knowledge in yeast genomics cam.ac.ukc.

Saplakoglu, Y. (2024). How AI revolutionized protein science – Quanta Magazine quantamagazine.org.

Wiggers, K. (2025). FutureHouse previews an AI tool for “data-driven” biology – TechCrunch techcrunch.com.

Huang, K., et al. (2025). Biomni: A general-purpose biomedical AI agent – bioRxiv (preprint) sciety-labs.elifesciences.orgsciety-labs.elifesciences.org.

Anthropic (2025). Biomni accelerates biomedical discoveries by 100x with Claude (Case Study) anthropic.com.

CAS (2022). AI drug discovery: assessing the first AI-designed drug candidates cas.org.

TechCrunch (2025). OpenAI exec leaves to found materials science startup techcrunch.com